The number of people needing an organ transplant increases each day, and so does the number of people dying as a result of not finding a donor in time. 3D printed organs could definitely change these facts.

Last year, researchers announced that 3D printing blood vessels is possible, so it’s no surprise that they expanded they focus to include organs in the list of things that can be manufactured this way. San Diego-based bio-printing company Organovo claims that they made significant advancements in the field, which means that they will be able to make the first 3D printed liver next year. That might seem a weird choice, as the liver is the only human organ capable of natural regeneration, and as little as 25% of it can grow into a full organ again. By all means, that doesn’t mean that this initiative is not important. It can revolutionize the medical field, thus encouraging others to look into 3D printed organs.

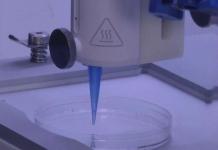

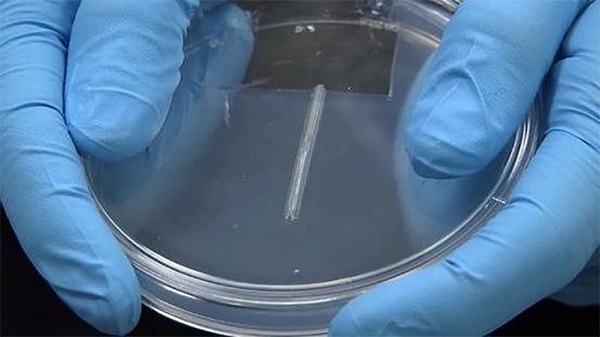

Bio-printing involves placing layer after layer of live cells until a new organ is formed. Mike Renard, Organovo’s executive VP of commercial operations, explained the progress his company has made: “We have achieved thicknesses of greater than 500 microns, and have maintained liver tissue in a fully functional state with native phenotypic behavior for at least 40 days.” There is still a doubt that the 3D printed organ would be able to develop properly inside the human body. Moreover, it is unknown how quickly it would react to drugs. Renard mentioned that “It is too early to speculate on the breadth of applications that tissue engineering will ultimately deliver or on the efficacy that will be achieved.”

The Methuselah Foundation even organized a contest with a $1M prize for the first company to create a fully functional 3D printed organ. David Gobel, the CEO of this foundation, pointed out that “Regenerative medicine is the future of health care, but right now the field is falling through the cracks”

Jordan Miller, assistant professor of bioengineering at Rice University, considers that “Using 3D printing has given us the reproducibility and the automation needed to scale up. It’s a complicated challenge. We don’t know all the structures in the body. We’re still learning. So we don’t know to what extent we need to reconstitute all those features. We have some evidence that we may not need to re-create all those functions.”

At this university, researchers are looking to create more than just liver tissue, as Miller says: “We’ve had some success in thin tissues, skin, corneas and bladder. It gets more complicated when you’re talking about biochemical functions in the liver or kidney. Those are fragile cells that don’t do well in labs. Some of the most interesting cells we want to print are hardest to keep alive.”

Supposing that such 3D organs prove to be viable, would people start making transplants even if they didn’t need to? The fear of having an organ fail at some point might determine some to do so. The price of such a transplant will probably be very steep, for the beginning, but things will most definitely progress.

If you liked this post, please check the Foodini pizza 3D printer and the fossils that can be 3D printed at home.