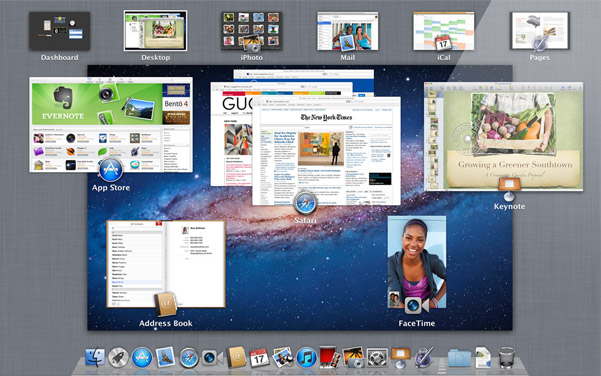

Apple has released OS X Lion packed with 250 new features bringing a more iOS like interface to the Mac. Is Lion worth the upgrade?

Apple is taking a large leap with OS X Lion, perhaps one of the most dramatic since OS X debuted in early 2000. The influence iOS has on Lion is apparent everywhere you turn in the interface and how you fundamentally interact with the underpinnings of your computer.

The goal of Lion is to bring everything great about iOS such as touch gestures, interface controls, the App Store to OS X and blur the line between a standalone file and content you interact with. This review won’t focus on picking apart individual features but rather how Lion functions as a whole and what it means for the future of OS X and even iOS.

The File System

IOS, while based on OS X and fundamentally UNIX, does not have a file system that the user can navigate. Apple’s stance on the file system has only become apparent when Lion was first shown last October.

How you interact with the file system in the traditional sense of you finding a file in a folder is starting to change in Lion. While that basic level of functionality is still present in Finder, Apple is going to great lengths to group files based on content type and which Applications interact with them. Apple is essentially dumbing down more complex elements of the file system.

During first use of the Finder you’ll see the familiar folder view in the sidebar albeit expanded but with three new additions: MobileBackups, AirDrop and All My Files. MobileBackups is a complement to Time Machine which stores data you have erased and versions of previous work. Only updates at the data level are saved to conserve space. Apps such as TextEdit and Pages which auto save data and snapshots of your work will put their data here. This works great if you have a mobile Mac and don’t carry your Time Machine drive with you wherever you go. Autosaving works exactly as you would expect and to further reinforce the integration between Time Machine and versions of files, Apple has removed the “Save As” function. Instead you’ll select “Browse All Versions” in the title bar of the respective App you want a previous version of a file for and choose from a list of previews.

All My Files is basically Apple’s expanded and limited replacement to you accessing your Hard Drive directly through the Finder. Apple has opted not to allow users to access the Hard Drive from the Finder and must enter through the icon mounted on their desktop. This is another step in Apple making the file system more content aware in Finder. Files aren’t sorted by extension but rather by which Application interacts with them.

AirDrop is file sharing dumbed down in to one, simple to use button in the Finder. When Macs running Lion are in nearby proximity and connected to the same network as you, they’ll appear in AirDrop view and files can be transferred between machines.

The Interface

Apple has touted how much of an influence iOS has made on the Mac. The interface in Lion looks different from previous versions of OS X and the iOS references aren’t subtle but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Multitouch gestures, inertia based scrolling and full screen Apps are all welcome additions but as mentioned above, the new interface is another step in Apple’s journey of blurring the distinctions between traditional OS interfaces and Lion which starts to lead the user away from the file system.

This has lead to a lot of modularity and separation in Lion. Spaces have been dumbed down significantly and are less intuitive to set up. Applications are assigned to Spaces, (or rather virtual desktops) from the Dock instead of the Dock and System Preferences. Virtual desktops are instead created on the fly and often times will revert to OS X’s default wallpaper on your main and secondary screen. Speaking of secondary screen, you may not find full screen Apps all that useful. Apple’s quick command to put an App in to full screen will blank out every screen but your main one with a nice, textured wallpaper – there’s no way around it unless you drag the length and height of a window to each edge of your display.

Touch gestures have been a growing feature in OS X starting with Apple’s multitouch compatible trackpads in later versions of the MacBook Pro and MacBook Air. In Lion, Apple has gone all out with gestures allowing you to interact with almost every aspect of OS X’s interface.

The swipe gestures shown on Apple’s website require some practice and repetition to remember. The only downside is the social awkwardness trying to pull of a successful gesture in public. Most touch gestures replicate quick keyboard commands but can be just as fast if you know your gestures and know what you want to do. For example, Alt + Tab will cycle through active Applications and is one of the most useful shortcuts on the Mac. That functionality is replicated by swiping three fingers through Spaces but if an App doesn’t exist in a space you’re sliding in to, you’ll need to keep going until you reach the window or App you’re looking for. Gestures and shortcuts can exist harmoniously – there really isn’t a wrong or right way to gestures, just whatever is most convenient for you. If you love using gestures, I would very highly suggest dishing out the money for a Magic Trackpad if you’re using a desktop based Mac.

The Future Of OS X

Lion is a huge step for OS X whether you agree with the direction Apple is going or not. The App Store will start to play a huge part in the OS X’s future as future OS updates are installed through an internet connection and subsequent updates such as 10.8, 10.9 and so on installed as components not requiring a complete wipe down of the OS and upgrade. Multitouch gestures along with Lion’s interface overhaul will make the Mac more touch intuitive but no where close to the touch experience found in iOS.

We’ll eventually see a greater migration from the file system we interact with each day in favor of Apps that access data it has created and has been told to interact with versus having complete control on where a file exists and which Apps accesses it.