Scientists don’t always know what they’re going to find out when they start experimenting. Quite often, they end up getting very different results from what they initially planned for, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

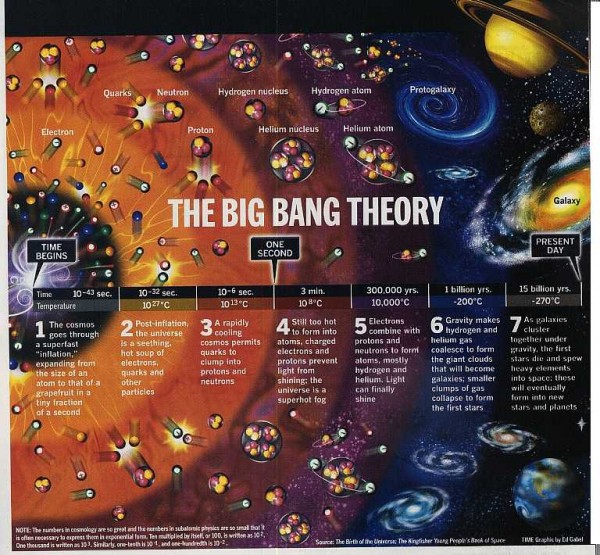

Big Bang

Robert Wilson and Arno Penzias, while working (in 1964) with the Holmdel antenna in New Jersey, discovered a background noise they couldn’t explain. After ruling out possible interference from urban areas, nuclear tests, or pigeons living in the antenna, Wilson and Penzias came across an explanation with Robert Dicke’s theory that radiation leftover from a universe-forming big bang would now act as background cosmic radiation.

Coca-Cola

John Pemberton, a pharmacist, used two main ingredients in his hopeful headache cure: coca leaves and cola nuts. His lab assistant mixed the two, by mistake, with carbonated water, and the world’s first Coke was the result.

Microwave

Percy Spencer was an American engineer who, while working for Raytheon, walked in front of a magnetron, a vacuum tube used to generate microwaves, and noticed that the chocolate bar in his pocket melted. It was invented in 1945 after a few experiments, but it took 22 years for the more compact models to begin invading American homes.

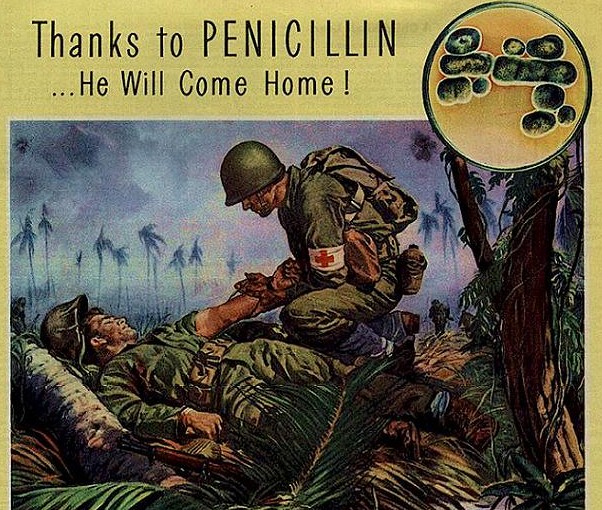

Penicillin

Alexander Fleming took an August vacation from his lab work investigating staphylococci, known commonly as staph. When he returned (September 1928) he found a strange fungus on a culture he had left in his lab—a fungus that had killed off all surrounding bacteria in the culture, and modern medicine was re-invented.

Alexander Fleming took an August vacation from his lab work investigating staphylococci, known commonly as staph. When he returned (September 1928) he found a strange fungus on a culture he had left in his lab—a fungus that had killed off all surrounding bacteria in the culture, and modern medicine was re-invented.

Radioactivity

In 1896, French scientist Henri Becquerel was working on an experiment involving a uranium-enriched crystal. He believed that sunlight was the reason that the crystal would burn its image on a photographic plate. With dark clouds rolling in, Becquerel packed up his gear and decided to continue his research on another sunny day. He retrieved the crystal after a few days, and image burned on the plate was fogged. The crystal emitted rays that fogged a plate, but were dismissed as weaker rays compared to William Roentgen’s X-ray.

Smart Dust

Chemistry graduate student Jamie Link was working on a silicon chip at the University of California. When the chip shattered, she discovered (with the help of her professor) that the tiny bits of the chip were still sending signals, operating as tiny sensors. Smart dust has a myriad of potential applications and plays a large role in attacking and destroying tumors.

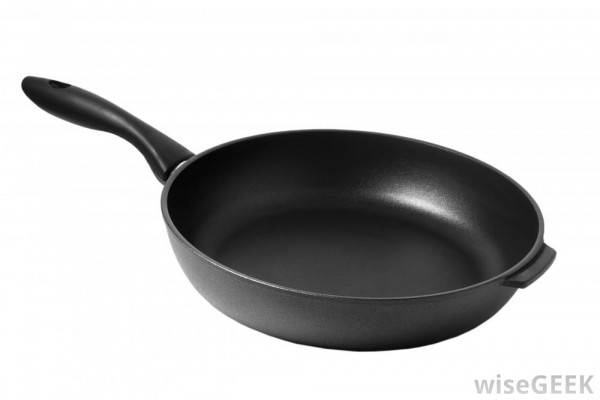

Teflon

In 1938, Roy Plunkett, a scientist with DuPont, was working on ways to make refrigerators more home-friendly, searching for ways to replace ammonia, sulfur dioxide, and propane, the current refrigerant at the time. He opened a container on one particular sample he’d been developing, discovering all the experimental gas was gone. All that was left was a strange, slippery resin that was resistant to extreme heat and chemicals. After being used in the Manhattan Project and the Automotive industry, it made its way to the kitchen.

Velcro

Swiss engineer Georges de Mestral found burrs clinging to his pants and also to his dog’s fur. On closer inspection, he found that the burr’s hooks would cling to anything loop-shaped. He artifically re-created the loops, and Velcro was invented. It took some time to catch on, but after NASA started using it in the 1960s, everyone did.

Viagra

The pharmaceutical company Pfizer developed a pill named UK92480 to help constrict these arteries to relieve pain. The pill failed its primary purpose, but the secondary side effect was startling. The drug became known as Viagra.

Vulcanized Rubber

After years of trial and error trying to make rubber more durable, Charles Goodyear accidentally dropped his rubber concoction on a hot stove. What he discovered was a charred leather-like substance with an elastic rim. Rubber was now weatherproof.

After years of trial and error trying to make rubber more durable, Charles Goodyear accidentally dropped his rubber concoction on a hot stove. What he discovered was a charred leather-like substance with an elastic rim. Rubber was now weatherproof.

For more on discoveries and ingenuity, check out these 9 inventors killed by their own inventions and 8 Inventions From the 1980?s That Never Took Off

Via: Techflesh